11.4 History Paintings

H1 – Adolf IV. von Schauenburg on his sarcophagus (restoration of the wooden panel from c. 1450)

In 1614, David Kindt was commissioned to restore the full-length portraits of Count Adolf IV of Schauenburg (before 1205-1238) from the middle of the 15th century, which were formerly in the Maria Magdalena Monastery in Hamburg.1 Today only the painting with the lying figure of the deceased count in the Minorite habit, which is in the Museum für Hamburgische Geschichte, has been preserved.

In 1227 Count Adolf IV defeated the Danes in the Battle of Bornhöved. Following this decisive battle, which took place on Mary Magdalene Day (22 July), the city of Hamburg formally recognised Count Adolf IV of Schauenburg as a lord of the city by receiving him inside the city walls. In the following years Count Adolf IV contributed much to the flourishing of the city. He donated several monasteries and churches. One of his foundations was the Maria Magdalena Monastery of the Franciscans. In 1239 Adolf IV travelled to Rome, was ordained a priest and then entered the Maria Magdalena Monastery, where he lived until 1247.2 The two paintings, which were made in the 15th century for the Maria Magdalena Monastery, showed the count standing full of armour as a secular prince and lying in his coffin in the habit of the Franciscans. Both paintings belonged together, as a copper engraving in Peter Lambeck’s Origines Hamburgenses from 1652 shows. Only the painting with the reclining figure has survived. The painting with the standing figure was destroyed during the bombing of Hamburg in 1943. Until this time, it was permanently in the possession of the Maria Magdalena Monastery. A photograph from the pre-war period shows that this painting, too, was restored or painted over around 1600 and provided with a new frame decorated with strapwork.3

H1

Hans Bornemann or Lüdeke Clenod Bohnsack and David Kindt

Adolf IV. von Schauenburg in his sarcophagus, c. 1450 and 1614

Hamburg, Museum für Hamburgische Geschichte, inv./cat.nr. AB 582

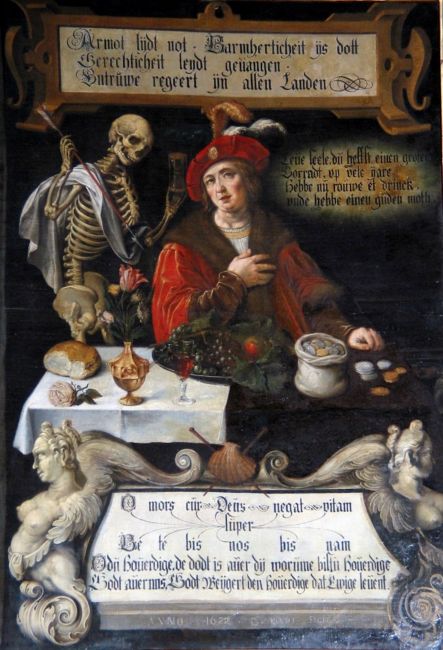

H2 – The Rich Man and Death, dated 1622

One of the paintings described by Gerson is a painting in St. Jacob’s Church, which David Kindt ‘restored’ in 1622.4 It is an allegorical painting signed by David Kindt in 1622 depicting Death and the rich man.5 Harry Schmidt follows the opinion of Faulwasser and Lichtwark that this work was painted by an unknown artist from the 16th century and that David Kindt only restored and partly overpainted it on behalf of the parish council.6 This view was also shared by Röver, who dated the painting at ‘around 1550’.7 Carl Schellenberg, on the other hand, was able to prove through a technical examination, including an X-ray, that the painting had not been painted over under any circumstances and that it must therefore be regarded as an original by the hand of David Kindt.8 It cannot be ruled out, however, that an older depiction of similar content served as a model.

The painting shows a man dressed in a precious red fur-trimmed coat and a beret adorned with long feathers. He sits at a table, the left half of which is covered with a white tablecloth. On the cloth stands a shimmering golden Venetian vase with five half-blossomed tulips and a glass filled with red wine. At the front edge of the table lies a cut rose and behind it a cut bread. On the right side of the table there is an open moneybag filled with coins and further scattered and stacked coins. Directly in front of the rich man stands a large plate loaded with fruit. Death in the form of a skeleton with an arrow in one hand and an hourglass in the other approaches the rich man from the left. He wears a shroud, draped over his shoulder like a sash. Three inscription fields explain the meaning of the painting. A longitudinal rectangular cartouche with strapwork and scrolls at the top bears the inscription:

Armot lijdt not · Barmherticheit ijs dott /

Gerechticheit leydt geuangen · /

Vntruwe regeert ijn allen Landen9

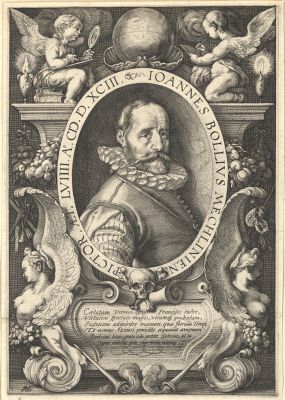

At the bottom of the painting there is an elaborate, trapezoid cartouche framed by two winged sphinxes. On the upper frame of the cartouche, between the wings of the sphinxes, there is a scallop with two pilgrim staffs. On the lower frame of the cartouche are the artist’s signature and the date 1622. David Kindt copied the sphinxes after a copper engraving by Hendrick Goltzius (1588-1616), showing the portrait of the painter Hans Bol (1534-1593) in an oval frame carried by winged sphinxes [H2a].

The inscription field contains a Latin pun in three lines:

O mors cur Deus negat vitam

super

Be te bis nos bis nam

The individual words and syllables, which do not make sense for themselves, are connected by lines pointing the way to the solution of the inscription:

O superbe – mors super te – cur superbis?

Deus super nos – negat superbis – vitam supernam10

The text is repeated again in Middle High German in the lower part of the cartouche:

O du houerdige, de dodt is auer dij worume bistu houerdige /

Godt auer uns, Godt weijgert den houerdige dat Ewige leuent.

To the right of the picture, at the height of the rich man’s head, there is another inscription in Low German. It is placed in a bright, not clearly defined, oval field and reads:

Leue seele, du heffst einen groten /

Vorradt, vp vele ijare, /

Hebbe nu rouwe et drinck, /

vnde hebbe einen guden moth.

It is taken from the Gospel of Luke: ‘Dear soul, you have a great supply for many years; now rest, drink and have good courage’.11 The Biblical quotation describes the life situation of the rich man who has accumulated a great fortune. The bread, the wine glass and the fruits seem to illustrate the meaning. In the context of the other two inscriptions, a moral sense emerges which, as memento mori, refers to the end of earthly existence and the transience of all earthly goods. The motif of the rich merchant who is struck by death in the middle of life goes back to the motif of the danse macabre. David Kindt abandons the medieval pattern of walking full-length figures and focuses on Hans Holbein’s pictorial inventions in his series of woodcuts on the Dance of Death, made around 1524.12 The still life-like arrangement on the table corresponds to the more recent form of representation of transience, which first appeared around 1600, and which, in the later 17th century, flows into its own genre with the Vanitas still life. The play De düdesche Schlömer by Johannes Stricker (1540-1599), which appeared in 1584 in Lübeck, can be considered as a literary model. It is an adaptation of the well-known play ‘Jedermann’ (Everyman) which has been known since about 1500: An unscrupulous rich man is condemned to early death by God and to eternal hell by Moses. As a dying man, he turns to God again and thereby achieves eternal live. The decisive factor for this turning point is the Protestant view that it is not good works but faith in God alone that makes the redemption of the soul possible. Related in content is also the story of the poor man and the rich Lazarus, written by Georg Rollenhagen (1542-1609) in 1590, which has produced its own pictorial tradition.

H2

David Kindt

The Rich Man and Death, dated 1622

Hamburg, Sankt Jacobi Kirche

H2a

Hendrick Goltzius

Portrait of Hans Bol (1534-1593), dated 1593

The Hague, RKD – Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Collectie Iconografisch Bureau)

H3 – The Lamentation of Christ, dated 1631

The Lamentation of Christ, now in the Louvre in Paris, is a mystery in many respects.13 On the one hand, the subject is unusual for David Kindt and, on the other, the concept of the theme seems quite antiquated for a 17th-century work. In earlier catalogues the painting was assigned to the school of Joos van Cleve (1485-1540). It was not until 1980 that the signature of David Kindt and the date 1631 were discovered during its restoration. The narrow, longitudinal, rectangular painting shows the body of Christ taken from the cross and laid on a smooth stone slab. The shroud lies under his stiff, slightly contorted body. His wounds no longer bleed and his nakedness is covered with a white cloth. There are five people near the body. The head of Christ is gently lifted by his mother Mary, who supports the neck of the deceased with her right hand. To her left is Joseph of Arimathia, depicted as an elderly man with a grey beard and bald head, wearing a brown robe. To the right of Mary stands John wearing a red cloak. His youthful face is furrowed with grief. He has folded his hands in prayer. To the right of John, by the legs and feet of the body of Christ, Mary Magdalene and Mary Cleophas are depicted. While Mary Cleophas, like Our Lady, wears a flowing, antique garment and a veil, the figure of Mary Magdalene stands out for her modern, rich clothing. Unlike the other women, her head is not covered. She wears her blonde hair tautly combed backwards and a coiffure with a braid. Over a delicate, translucent undergarment with golden piping she wears a dark red coat with fur trimming. With her right hand she grabs her forehead, with her left she holds the jar of ointment. Her attentive gaze is directed at the corpse, but David Kindt refrains from depicting any signs of exalted mourning. It seems very unusual that the theme was even depicted in Lutheran Hamburg, since this subject is rarely found in Protestant regions.

H3

David Kindt

The lamentation of Christ, dated 1631

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv./cat.nr. 20747

H4 – Landscape with the Entrance of Christ into Jerusalem, dated 1643

The entry of Christ into Jerusalem is a broad landscape with a procession approaching the gates of Jerusalem.14 Christ, riding on a donkey, is accompanied by his disciples, who swing palm branches. The composition of the landscape roughly follows the motifs of a series of engravings by Hans Sadeler (1550-1600) after drawings by Paul Bril (c. 1553/54- after 1600). The scene with the entry into Jerusalem, however, was added independently by David Kindt.

H4

David Kindt

Landscape with the Entrance of Christ into Jerusalem, dated 1643

Prague, Národní Galerie v Praze, inv./cat.nr. O 2557

Notes

1 Hans Bornemann or Lüdeke Clenod Bohnsack, Adolf IV. von Schauenburg as monk, c. 1450, oil on panel, c. 124 x 277 cm, Museum für Hamburgische Geschichte, inv. AB 582. Literature: Lichtwark 1898, p. 73-78; Möller 1977, p. 14, 36ff; Landt 1988, p. 7-15; Beiner-Büth 1988; Jaacks 1992, p. 228; Schneede/Giesen et al. 1999-2000, vol. 1, p. 174ff, no. 17.

2 Bracker 1989, vol. 1, p. 244; Loose 1982, p. 17-100; Urbanski 1999-2000.

3 Schneede/Giesen et al. 1999-2000, vol. 1, p. 174, figs. 1 and 2.

4 Gerson 1983/1942, p. 218ff.

5 David Kindt, The rich man and death, 1622, oil on canvas, c. 136 x 93 cm, signed and dated on the lower margin ANNO. 1622. D. KINDT. FECIT, Hamburg, St. Jacob’s Church. Literature: Lappenberg 1866, p. 298ff; Faulwasser 1894, p. 95; Lichtwark 1898, vol. 1, p. 93-96; Schmidt 1919, p. 30ff; Röver 1928, p. 293; Schellenberg 1942, p. 276-284; Klée Gobert 1968, p. 216, no. 292; Mohaupt 1982, p. 54ff; Bracker 1989, vol. 2, p. 450ff, no. 20.31; Steiger 2016, vol. 1, p. 352ff.

6 Faulwasser 1894, p. 95; Lichtwark 1898, p. 96; Schmidt 1919, p. 30ff.

7 Röver 1928, p. 293.

8 Schellenberg 1942, p. 276.

9 Poverty suffers hardship/Mercy is dead/Justice is imprisoned/Infidelity reigns all over the country. Lappenberg brings this Low German poem into connection with other church-critical and socio-critical Low German rhyme poems from the Reformation period (Lappenberg 1866, p. 298, see also Lappenberg 1847).

10 Oh, you haughty man! Death is upon you, what are you rising up for? God above us denies eternal life to the arrogant. Lappenberg refers to the model of an older inscription on a tombstone in the Cathedral of Hamburg (Lappenberg 1866, p. 298, note 2). The inscription is recorded by Anckelmann (Anckelmann 1663, p. 73, CXIV).

11 Luke 12, 19.

12 On the danse macabre in medieval and early modern time: Rosenfeld 1954/1974 and Rosenfeld 1966; Dreier 2010; Oosterwijk/Knöll 2011.. On Hans Holbein’s death dance: Petersmann 1983 and Goette 1897/2013.

13 David Kindt, Lamentation of Christ, 1631, oil on canvas, c. 57.5 x 155 cm, Musée du Louvre Paris, inv. 20747, signed and dated DAVID KINDT F. 1631. Provenance: unclear; remained in the Louvre in 1941 as ‘school of Joos van Cleve’. Foucart-Walter et al. 2013, p. 136.

14 David Kindt, Landscape with the Entrance of Christ into Jerusalem, 1643, oil on panel, c. 56 x 85,5 cm, signed and dated on the tree trunk right: 1643, DKIND (in ligation), National Gallery Prague, inv. O 2557. Provenance: before 1920 Russian private property; around 1920 Collection Schall Berlin-Wilmersdorf; 1925 offered for sale by Erich Schall to the Hamburger Kunsthalle; art market; before 1943 Collection V. Burda, Prague; 1943 purchased by the National Gallery Prague. Literature: Schmidt 1928; Gerson 1942/1983, p. 219; Cat. National Gallery Prague 1949, p. 50, no. 329; Cat. National Gallery Prague 1955, p. 51, no. 324; Cat. National Gallery Prague 1960, p. 49, no. 344; Šip 1967, p. 42, no. 39; Geissler 1979, p. 135; Seifertová 1989, p. 49ff, no. 30; Seifertová in Cat. National Gallery Pilsen 1989, no. 19; Slaviček 2000, p. 409; Jandlová Sošková 2015, p. 72ff, no. 45.