10.2 Natural and Immediate : The Small Landscapes

The Small Landscapes are in many respects a corpus that defines a certain type of landscape, making them hugely influential for several generations of artists. They are somehow unique and interesting, as has been pointed by countless commentators. Nils Büttner goes even further when he observes that there is also ‘das Unscheinbare’, an element of not being clearly visible or inviting attention, which attracts the artist’s eye. An unobtrusive stretch of land or an unremarkable feature within the native landscape can so become an all-encompassing topic.1 Walter S. Gibson describes their simplicity as ‘seemingly artless arrangements’ and is absolutely right. ‘In some views,’ he continues, ‘the terrain, trees, and buildings are arranged roughly parallel to the picture plane; others are dominated by a foreshortened perspective movement into depth’.2 In their unadorned simplicity, as Hans-Martin Kaulbach has put it so succinctly, ‘the pictures are being transformed and freed, bringing them closer the prosaic material world’.3 And in that respect the Small Landscapes are markedly different from other early landscape prints that modern art critics may value more for their artistic merit, or what they perceive to be a greater achievement.

A classic example are the works of Albrecht Altdorfer (c. 1480-1538) and Augustin Hirschvogel (1503-1553). Both names are mentioned by the 17th-century painter and art writer Joachim von Sandrart who briefly touches upon Augustin being the successor of his father Veit. The entry on Altdorfer in the Teutsche Academie is slightly longer, describing his life and emphasising the artist’s ‘talent of drawing small pictures’, albeit without commenting on Altdorfer’s landscapes.4 The difference between the two afore-mentioned artists and the master of the Small Landscapes can be best illustrated by looking at Altdorfer’s Landscape with two-trunked spruce tree (Landschaft mit Doppelfichte) [4].5

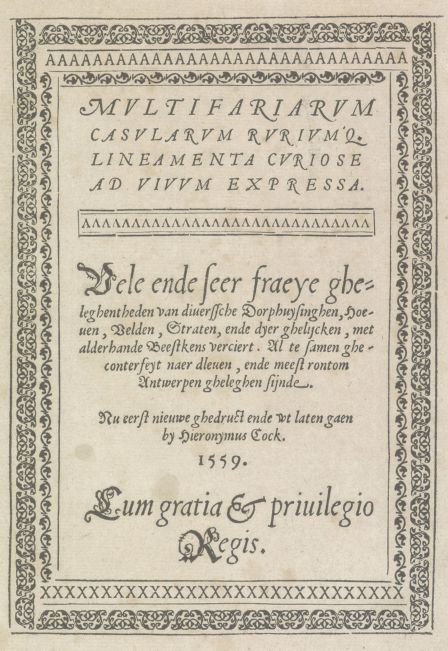

This iron etching was made circa 40 years before the Small Landscapes and is similar in format; yet it needs the viewer to engage with it differently. It is, of course, true that, in principle, any depiction of landscape that is not defined on each side by a framing tree requires the viewer to use his imagination to explore what is beyond the boundaries of the image. Most of the prints of the Small Landscapes are no exception and belong to the same type. Altdorfer’s Landscape with two-trunked spruce tree, however, has been designed to open it up vertically towards the sky. The tree, cropped by the border, and the sky being left white seem to intensify the atmosphere, making the viewer speculate over what the actual height of the giant tree is and what it looks like at the top. The various settlements and mountain ranges inserted to the left and right of the picture do not establish a clearly defined horizontal border either. It is therefore not surprising that, as regards to the etching and its compositional design but also to the artist’s monogram in a prominent place, Altdorfer’s print stands out as an important contribution to the genre. There is no doubt that his work was revolutionary,6 but this is also likely the reason why it never achieved the renown of the Small Landscapes (or what we assume their popularity to be). This is mainly due to their publication history (for example, draughtsman and engraver are not the same person, and the composition seems to serve a pragmatic rather than an aesthetic purpose) but also to the fact they were conceived (or at least appeared) as a whole series of prints. And even though they lack a certain individuality in their formal design and are less demanding on the viewer, the interest they aroused in the minds of both sellers and buyers was most likely further heightened by the relation to a precise geographical region that is established in the title page of the prints: ‘Vele ende seer fraeye gheleghentheden van diuerssche Dorphuysingen […] ende meest rontom Antwerpen gheleghen sijnde’ [5-8].

4

Albrecht Altdorfer

Landscape with double spruce, between 1506-1522

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-2980

5

published by Hieronymus Cock

Title page for the ''Small Landscapes'' series by Jan and Lucas van Doetecum engraved and published by Hieronymus Cock in Antwerp, dated 1559

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-75.219

6

Joannes van Doetecum (I) or Lucas van Doetecum after Meester van de Kleine Landschappen after Master of the Small Landscapes published by Hieronymus Cock

Village street with hay wagon, between

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-75.237

7

Joannes van Doetecum (I) or Lucas van Doetecum after Meester van de Kleine Landschappen after Master of the Small Landscapes published by Hieronymus Cock

Farmhouse and house with stepped gable, between

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-75.233

8

Joannes van Doetecum (I) or Lucas van Doetecum after Meester van de Kleine Landschappen after Master of the Small Landscapes published by Hieronymus Cock

Village street with couple resting on a tree trunk, between

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-75.236

Notes

1 Büttner 2000, p. 179: ‘Vielmehr gelang es diesem Zeichner, ein nah gesehenes Einzelmotiv zu einem erschöpfendem Bildthema zu erheben. Das Interesse an der landschaftlichen Aufnahme heimischer Natur ließ den zeichnenden Künstler das Unscheinbare beachten, […].’

2 Gibson 2000, p. 10; also Brown 1986, p. 18ff.

3 Kaulbach 2003, p. 358: ‘In ihrer Einfachheit und Schmucklosigkeit bieten sie die Befreiung des Bildes zur schieren, prosaischen Gegenständlichkeit’.

4 http://ta.sandrart.net/-text-448 (10 Jan 2018), and Altdorfer being ‘gut in kleinen Bildern’.

5 Winzinger 1963, p. 116ff, no. 179. Winzinger only lists nine landscape etchings by Altdorfer and argues for dating them between 1517 and 1520. The early art literature does not mention the prints, and there is only vague reference to them in Sandrart. Wood 1993, p. 261-266, discusses the prints’ proportions, their meaning, and their fictional aspect.

6 Wood 1993, p. 234: ‘They were revolutionary landscapes but they ignited no revolution. […] Any influence that Altdorfer’s landscapes exerted was indirect, through the agency of these epigones’ [i.e. Augustin Hirschvogel and Hans Lautensack].