1.5 The Mobility of Artists from the Low Countries in the German Lands

In the context of the Gerson Digital project on the German lands, the Archduchy of Austria, and Bohemia, the project team updated or entered the profiles of more than 900 Dutch and Flemish artists of the early modern period in RKDartists&. The main focus was to document their mobility in the German lands as elaborately as possible, using all available literature and online sources.1 Many of the 17th- and 18th-century Dutch artists also play a role in the publication Gerson Digital : Germany, Austria and Bohemia, which was launched at the 2017 symposium Masters of Mobility.

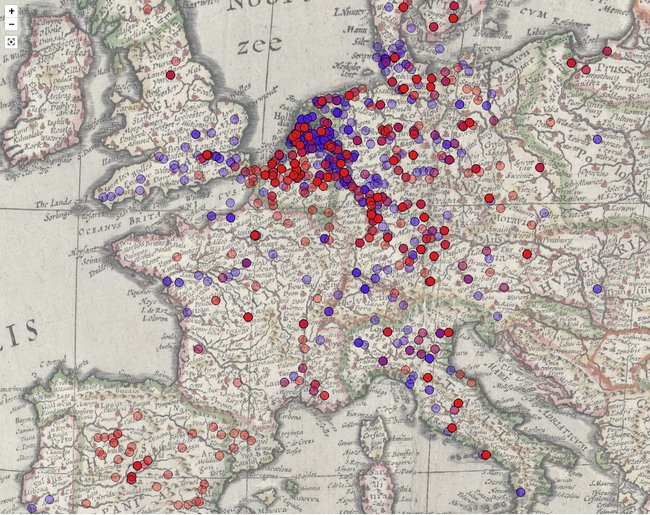

When we have a look at the dispersal of artists from the Low Countries in Germany [22], represented here in dots indicating the whereabouts of Dutch and Flemish artists (respectively in blue and red), we see a concentration of dots along the Rhine, the most important thoroughfare of the country. The dots do not only indicate towns and courts, but also picturesque places that were captured in drawings by dozens of artists on their way. One of the many ‘points of interest’ along the river Rhine was for instance Wesel [23], or – more spectacular – Rölandseck and Drachenfels.2 Netherlandish artists, especially from the Northern Netherlands, went for shorter wanderings across the German border to draw motifs they could use later on in their paintings at home. From their drawings, we can trace the routes they took.3 Many of them carried on to more distant places in Germany or beyond, others were satisfied with the impressions they found closer by and returned home.

As we saw above, Germany was by far a more popular destination for artists from the Northern Netherlands than it was for artists from the Southern Netherlands. Of the migrating artists, 30.52% of the travelling artists from the Northern Netherlands stayed in Germany, against 20.64% of the Southern Netherlandish artists.4 Also within Germany, it turns out that, generally speaking, Northern Netherlandish artists went more to the north of Germany, and the Southern Netherlandish ones to the south. Protestant artists were more inclined to stay in Protestant places, or places where Protestantism was tolerated, while Catholic artists preferred to take their chances in Catholic towns and courts. This image becomes even stronger when we include Austria and Bohemia, regions that were included in Gerson’s chapter on the German lands.5 By selecting the Netherlandish activity in RKDartists& in the Germany, Austria and the Bohemia, we find 36.31% of the mobile artists from the Northern Netherlands and 31.25% of the ones from the Southern Netherlands.6

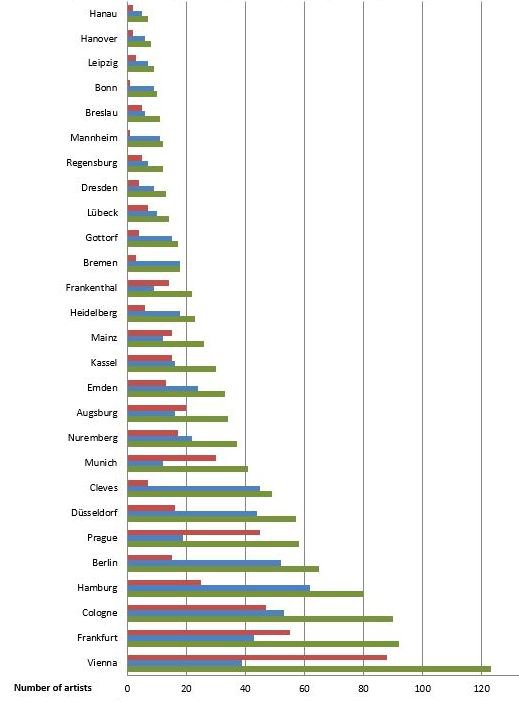

Which places were the most popular? A descending chart bar extracted from the data in RKDartists& shows the towns and courts where most artists from the Low Countries stayed [24-26]. Almost half of the indicated places in the chart bar are courts, to which foreign artists could sell their works freely; this could be more difficult in towns were artists had to become citizens and were restricted by guild rules. It is evident that artists from the Northern Netherlands show quite different destinations within this realm compared to artists of the Southern Netherlands and, when visiting the same towns, they did so to a different degree. The many different courts attracted predominantly Dutch artists when there were strong political and religious connections with the Northern Netherlands; Flemish artists formed a vast majority at courts which were connected to the Southern Netherlands. The many courts in the region of the Holy Roman Empire generated a vast amount of commissions for artists; according to Brulez, most commissions in Europe (28.5% of all) came from Germany.7 This corresponds with the substantially higher than average percentage of court artists from the Low Countries active in Germany, as retrieved from RKDartists&, which is 25.07%, against the average of 15.3%.8 This percentage of court artists is a little higher in the whole region of Germany, Austria and Bohemia, that is 25.81%, of which artists from the Southern Netherlands have a slightly larger share.9

In his ‘Ausbreitung’, Horst Gerson divided the region of Germany, Austria and Bohemia into six areas - Northern Germany, the Rhineland, Central Germany, the Main area, Southern Germany and Austria and Bohemia - each of which he discussed, so to speak, ‘clockwise’, from Northwest to Southeast. All the towns and courts in the illustrated chart bars are covered, including their specific circumstances and major actors and stakeholders. As in Gerson, in my research several artists on the move pop up in different places in the illustrated chart bars.

22

The dispersal of Dutch (blue) and Flemish (red) artists until 1800

Source: RKDMaps and RKDartists&, reference date February 2019

23

Anthonie van Croos

View of the town of Wesel on the Rhine river, with a draughtsman in the foreground

24

Artists from the Netherlands active in towns and courts in Germany, Austria and Bohemia until 1800 (red is Flemish, blue is Dutch, green is both)

Source: RKDartists&, reference date February 2019

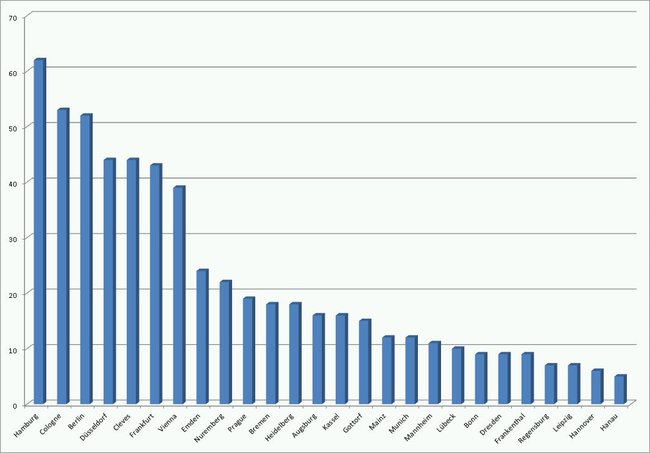

25

Northern Netherlandish artists active in towns in Germany, Austria and Bohemia until 1800

Source: RKDartists&, reference date February 2019

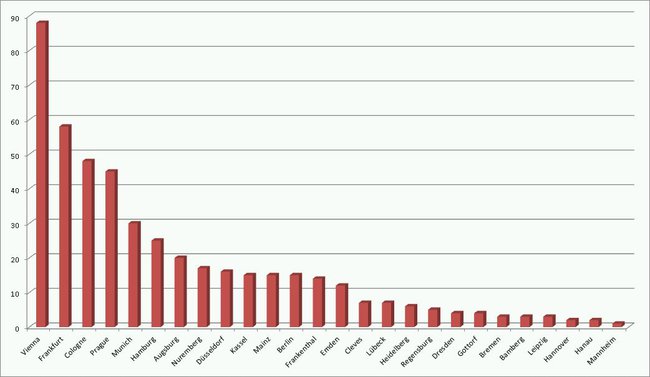

26

Southern Netherlandish artists active in towns in Germany, Austria and Bohemia until 1800

Source: RKDartists&, reference date February 2019

The town most frequently visited by Netherlandish artists was Vienna, which was mainly due to the activity of Flemish artists for the Viennese court, especially that of Leopold Wilhelm Archduke of Austria (1614-1662) [27], who was stadholder of the Spanish Netherlands in Brussels before he returned to Vienna in 1656, and his nephew Emperor Leopold I (1640-1705). For their Dutch colleagues, Vienna came only number six in their top ten of most visited places.

With Hamburg, the situation was reversed. The Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (including Hamburg-Altona) was the most visited town in the Roman Empire by Northern Netherlandish artists, not only because of its easy accessibility by water.10 Hamburg was booming: its economy developed rapidly, apart from disruptions during the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) and after the Great Northern War (1700-1721). The population grew from 20,000 in 1550 to over a 100,000 in the 1780s. Despite the fact that Hamburg was Lutheran and that non-Lutheran Protestants and Catholics were discriminated against in many ways, Hamburg was a fairly open city, that ‘wavered between openness and intolerance’.11 Nevertheless, is was still, ‘the most “open” city in the Holy Roman Empire’ for migrants and minorities. Some of the tension in Hamburg was eased by the religious freedom in nearby Altona. The difficulties the Catholic painter Dirk Stoop (c. 1618-1686) from Utrecht encountered while living in Hamburg, is illustrative. He settled in Hamburg after 1665 and it took him at least 14 years before he was finally accepted as a free master by the Hamburg painters’ guild. Together with a group of 19 other painters, he was engaged in legal proceedings against the Hamburg painter's guild in 1667 [28]. In 1674 he was working for the government of the cathedral in Hamburg, against which the painters’ guild protested. Finally, in 1681, the guild granted him the freedom to work in Hamburg and promised to invite him to all their meetings; at that time Stoop was already way into his sixties.12 When religion was not a problem, artists from the Low Countries could settle in a German town and be allowed to work there as a guild member, which many did. Hamburg was number six in the choice of destinations of Flemish artists, in particular before 1600, as a place of refuge.13

Cologne and Frankfurt scored highly for both the Northern and Southern Netherlandish artists. Although Cologne was primarily Flemish in orientation, the town also attracted a flow of Dutch Rhine-travellers, in particular from the 1650s onwards.14 Frankfurt was equally important for Dutch and Flemish artists because of its famous trade fairs, as an important production centre of books and prints and as the most important traffic hub in Germany. The Merian and Le Blon families in Frankfurt were highly active in the middle of this, as they were strongly connected to both the Southern and the Northern Netherlands.15 The well-travelled, reputedly pleasant and hospitable Matthäus Merian II (1621-1687) [29], who had been a pupil of Joachim von Sandrart in Amsterdam and a collaborator of Sir Anthony van Dyck in London, received a succession of artists in transit from the Low Countries in his house in Frankfurt, among others Samuel van Hoogstraten in 1651.

It was the Dutch artists who were predominant at the courts in Berlin and Düsseldorf, thanks to the Dutch connections of a few electors. Friedrich Wilhelm von Brandenburg (1620-1688), who had studied in Leiden and married Louise Henriette van Nassau (1627–1667), daughter of Frederik Hendrik van Oranje-Nassau and Amalia van Solms, attracted a series of Dutch artists to his court in Berlin.16 This tradition was continued by his son and successor Friedrich III, the future King Friedrich I von Preußen (1657-1713), who also founded an art academy in 1696 with the deployment of mainly Dutch artists. The Düsseldorf court, especially the one of Elector Johann Wilhelm von der Pfalz (1658-1716) was highly popular amongst Dutch artists.17 Some of them were even allowed to work largely in the Netherlands and only visit occasionally; among them was Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750), who travelled several times up and down from Amsterdam to Düsseldorf.18 Also the painting gallery the elector assembled during his lifetime was an important attraction for later generations of artists from the Netherlands in the 18th century.

The Catholic courts in Prague – especially the court of Emperor Rudolph II (1552-1612) – and Munich, on the other hand, employed mainly artists from the Southern Netherlands, more than twice as much artists as from the Northern Netherlands; in the top ten of places to go for Flemish artists in the Holy Roman Empire, Prague and Munich score respectively as number four and five.19

27

Peter Thijs (I)

Portrait of archduke Leopold Wilhelm von Habsburg (1614-1662) as commander-in-chief, c. 1650-1656

Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, inv./cat.nr. 370

28

Dirk Stoop

Grotto Interior with an Classical Ruins and Travellers, dated 1667

29

Matthäus Merian (II)

Self-portrait of Matthäus Merian II (1621-1687) with a head of Seneca, c. 1645-1646

Frankfurt am Main, Historisches Museum Frankfurt

Notes

1 German artists who were active in the Netherlands were documented too, as well as German patrons and collectors of Dutch and Flemish art.

2 Gerson/Van Leeuwen et al. 2017-2018, § 1.4 with references recent literature.

3 Laurens Schoenmaker (RKD) is preparing an article on the reconstruction of such a wandering in the Cleves area by Jan de Beijer (1703-1783).

4 Respectively 487 of 1,545 and 291 of 1,410 (retrieved February 2019).

5 The annotated text on Austria and Bohemia was added in September 2018 (Gerson/Van Leeuwen et al. 2017-2018, § 7).

6 Respectively 561 of 1,545 and 450 of 1,410 (retrieved February 2019). To filter Netherlandish artists in these regions in the database RKDartists, we have to be content with selecting Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic, as the geographic thesaurus of the database follows contemporary topography.

7 Brulez 1986, p. 44.

8 This is 25.25% for the Northern Netherlands artists and 23.86% of the Southern Netherlandish ones. The average percentage of travelling artists who were active at court has been calculated as 15%, see § 1.4.

9 This is 25.48% for the Northern Netherlands artists and 26.06% of the Southern Netherlandish ones.

10 On migration of artists between Hamburg and the Netherlands: Walczak 2011. Walczak takes the text of Horst Gerson as his point of departure.

11 Whaley 1995, p. 180, 188. See also: Pelus-Kaplan 2013.

12 Ed. Trautschold in Thieme/Becker 1907-1953, vol. 32 (1938), p. 113. Other sources state that he was born c. 1610, which would even make him about 71 when he was finally accepted in the Hamburg guild. Most sources state he that he died in Utrecht in 1686, or after 1681. However, Stoop is not listed in the death registers of Utrecht until 1725 and it seems likely he died in Hamburg. On the ‘Bönhasen-Prozess’: Bastian 1984, p. 33-35.

13 On the second generation immigrant artist David ‘t Kindt in Hamburg, see the contribution by Barbara Upperkamp (§ 11).

14 Gerson/Van Leeuwen et al. 2017-2018, § 1.4. On Flemish artists in Cologne: Vey 1968 and Veldman 1993.

15 On the networks of the Le Blon and Sandrart families, see the contribution by Johannes Müller (§ 3).

16 Gerson/Van Leeuwen et al. 2017-2018, § 2.8-2.11. On Dutch architects and engineers working for Friedrich Wilhelm in Berlin, see the contribution by Gabri van Tussenbroek (§ 5).

17 Gerson/Van Leeuwen et al. 2017-2018, § 3.4.

18 She named her 10th child Jan Wilhelm (baptized 21 July 1711) after her patron. The Elector and his wife Maria Anna Luisa de' Medici were the godparents On the activity of Rachel Ruysch for Johann Wilhelm, see the contribution by Anna Koldewij (§ 6). Ruysch is the most well-known of the seven women artists in my dataset of 728 travelling artists from the Low Countries who went to Germany. Vice versa there were eleven (out of 520), of whom Maria Sybilla Merian (1647-1717) is the most well-known. Reference date: February 2019. Research into the poet and actress Cornelia de Vlieger (1630-after 1668), who was thought to be a paintress active in Amsterdam, turned out to be the male painter Eltie de Vlieger (active c. 1690-1706), probably working in Hamburg (Van Leeuwen/Nijboer 2018).

19 On (Netherlandish) artists in Prague: DaCosta Kaufmann 1988 and Vienna 1988-1989. See also Gerson/Van Leeuwen 2017-2018, § 7.1. On Netherlandish artists in Munich: Vigneau-Wilberg 2005. See also Gerson/Van Leeuwen 2017-2018, § 6.6.