6.3 Interest from Leipzig

Elector Johann Wilhelm was not the only international collector who was enchanted by Ruysch’s still lifes: other German art collectors also acquired her work throughout the 18th century, as illustrated by two key examples of early German collecting below.

The aforementioned traveller Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach wrote that they were very lucky to have seen two finished still lifes by Ruysch: he explains that she made only about two paintings a year, and her work was so widely admired that orders were placed a year in advance. The finished paintings they saw were commissioned by Pieter de la Court van der Voort (1664-1739) [20] in Leiden, who was a highly esteemed collector in the Netherlands. Ruysch even considered the commission worth mentioning to her biographer Johan van Gool in 1750, about 40 years after the commission by De la Court was delivered.1 That could mean that this was one of the very few, or perhaps the most well-known large art collections in the Netherlands she received a commission from.

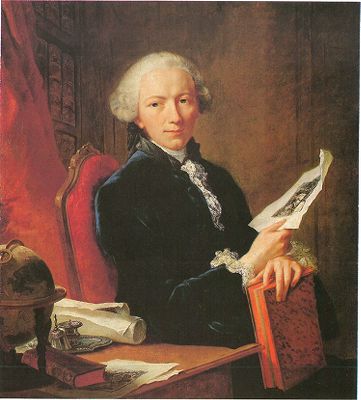

20

attributed to Willem van Mieris

Portrait of Pieter de la Court van der Voort (1664-1739), dated 1708

Leiden, private collection Allard de la Court

21

Arnold Boonen

Portrait of Allard de la Court (1688-1755), probably 1713

Amsterdam, Amsterdam Museum, inv./cat.nr. SB 2529

22

Arnold Boonen

Portrait of Catharina Backer (1689-1766), dated 1713

Amsterdam, Amsterdam Museum, inv./cat.nr. SB 2530

Remarkably enough, these paintings, so admired by Von Uffenbach, were exported to Germany about half a century later. The large and famous collection of Pieter de la Court was inherited by his son Allard de la Court (1688-1755) and his wife Catharina Backer (1689-1766) [21-22]. Catharina was an amateur still life painter herself, and can be considered a follower of Ruysch [23]. After Catharina’s death in 1766, the art collection was brought to auction. Many details about it can be found in an inventory written by Allard de la Court dated 1749 and in the 1766 auction catalogue. In 1749 the two paintings by Ruysch were recorded as: 102. ‘Bloemstuk’ (flower piece), 1710, bought for 650 guilders and sold for 1010 guilders; and 103. ‘Fruitstuk’ (fruits piece), 1710, bought for 650 guilders and sold for 1015 guilders. Von Uffenbach had mentioned a higher purchase price, of 1500 guilders each for both works but in either case, the paintings’ value had already increased enormously in less than 40 years – a trend that continues until the present day.

The still lifes by Ruysch, together with ten other paintings from the De la Court collection, were purchased by the German collector Gottfried Winckler II (1731-1795) [24]. Winckler was a merchant from Leipzig, who amassed a very large art collection which built upon that of his father Gottfried Winckler the Elder (1700-1771).2 About 1,300 paintings, 2,500 drawings, 80,000 prints, 6,800 books and a cabinet filled with gems were housed in his family home, Katharinenstrasse 22, and in his ‘Gartenhaus’. The building at the Katharinenstrasse housed most of the collection. This part was open to the public on Wednesday afternoons and provided employment for two staff members: an attendant during opening hours, and a curator called Franz Wilhelm Kreuchauff (1727-1805). After the death of Gottfried Winckler in 1795 his three sons split up the collection and sold most of it in batches over time. Thanks to the collection catalogue published by curator Kreuchauff in 1768, we still know the content of Winckler’s original collection. The 218 paintings at the private Gartenhaus were painted on eight aquarelles by the artist Christian Friedrich Wiegand (1748-1824) [25]. The two paintings by Ruysch were not included, which means that they must have been publicly exhibited in the Katharinenstrasse. Both pendants were sold separately by Winckler’s heirs, and have been own by different private collectors ever since.3 The whereabouts of the still life with fruits have been known for a long time [26], whereas the flower still life has quite recently been rediscovered and sold by Sotheby’s London in 2013 [27].

23

Catharina Backer

Flower still life, before 1711

Leiden, Museum De Lakenhal, inv./cat.nr. S 2332

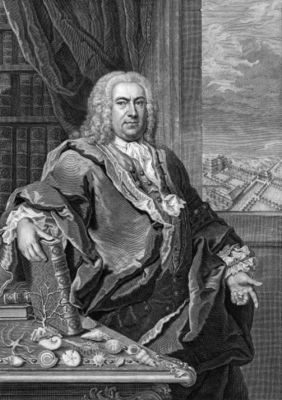

24

Johann Heinrich Tischbein (I)

Portrait of Gottfried Winckler II (1731-1795), dated 1757

Private collection

25

Christian Friedrich Wiegand

A wall of the collection Gottfried Winckler in Leipzig, c. 1770

Leipzig, Stadtgeschichtliches Museum Leipzig

26

Rachel Ruysch

Still life of fruit with insects and a birds nest on a mossy bank with pebbles, 1710 (dated)

London (England), Munich, art dealer Konrad O. Bernheimer

27

Rachel Ruysch

Still life of roses, tulips, a sunflower and other flowers in a glass vase with a bee, butterfly and other insects upon a marble ledge, dated 1710

London (England), art dealer Hazlitt

Another important painting collection in Leipzig emerged at the same time as Winckler’s galleries to become a ‘friendly competitor’.4 Merchant Thomas Richter (1652-1719) earned his wealth in the cobalt blue trade: a profession he passed down to the next generation. His both sons, Johann Zacharias Richter (1696-1764) and Johann Christoph Richter (1689-1751), participated in the family business and became collectioneurs to continue existing profitable international relations. Their clients must have had a common interest in rare natural raw materials used as ingredients for paint. Johann Christoph collected so called naturalia, natural artefacts, which he exhibited in his Museum Richterianum [28]. His elder brother Johann Zacharias collected paintings, drawings and prints. When this last collection was inherited by his son Johann Thomas Richter (1728-1773) in 1764, it was expanded to include c. 400 paintings, c. 1000 drawings and a few thousand prints, and it was made accessible to the public.5 The collection included two small pendants – a flower piece and a still life with fruits – by Rachel Ruysch [29-30].6

The appearance of two pairs of still lifes by Ruysch in these contemporary Leipziger collections does not seem to be a coincidence: Johann Thomas Richter had made a ‘Grand Tour’ in his younger years, together with Gottfried Winckler. This journey through the Netherlands, England, France, Southern Germany and Italy, must have been the inspiration for the both of them to start collecting art themselves, taking over their fathers’ interests. Unfortunately, details of their activities in the Netherlands are unknown, but they must have seen Rachel Ruysch’s work during this trip – and they might even have visited her.

28

Johann Martin Bernigeroth after Ádám Mányoki

Portrait of Johann Christoph Richter (1689-1751) showing some of his collected naturalia, between 1751-1767

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1914-1708

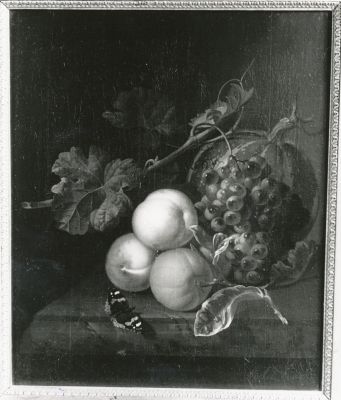

29

Rachel Ruysch

Still life of peaches, grapes, a bitter orange and a squash, with a red admiral, on a marble ledge, c. 1710

Eichenzell, Schloss Fasanerie, inv./cat.nr. B 408

30

Rachel Ruysch

Flowers in a glass vase, with a dragonfly, on a marble ledge, c. 1710

Eichenzell, Schloss Fasanerie, inv./cat.nr. B 407

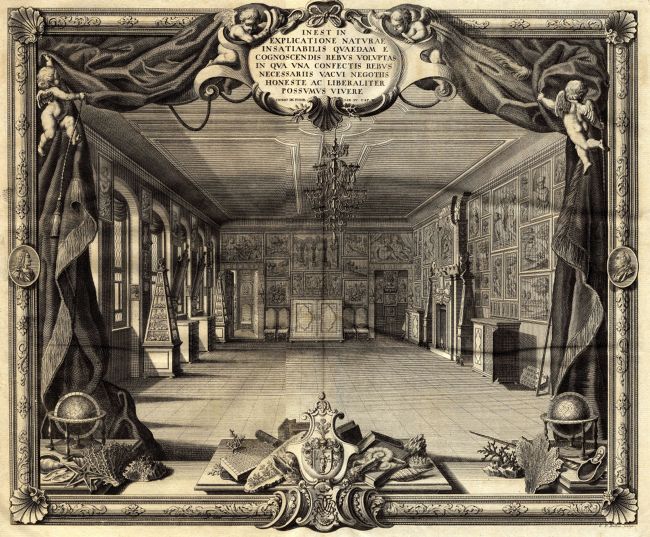

The content of the Richter art collection is known thanks to an auction catalogue, created in 1810 when the collection was sold by the heirs of Johann Thomas’ son Johann Friedrich Richter (1729-1784).7 No descriptions of the collection in its original form are known, however, there is a print at the beginning of the published catalogue of Johann Christoph Richter’s naturalia collection that seems to provide an insight in the main exhibition room of the Museum Richterianum [31], although this could also be a fictional rendition.8 In either case, it gives an idea of how Johann Zacharias and Johann Thomas may have displayed their collection, which was partly exhibited in the Bosehaus at the Thomaskirchhof in Leipzig and partly in their ‘Gartenhaus’ at the Gerberstraβe. Following the 1810 auction, the paintings were acquired by the painter Christian Nathanael Fischer (1756-1817) of Leipzig. Following this acquisition, the works were lent to a charity exhibition for the benefit of the victims of the Leipziger Völkerschlacht, the Battle of Leipzig (1813), in 1814.9 In 1820 Fischer’s art collection was sold by auction in Leipzig and the Ruysch pendants were bought by collector Heinrich Wilhelm Campe (1771-1862), who was also based in Leipzig.10 His collection was sold by auction in 1827, when these paintings were sold to Wilhelm II (1777-1847), Elector of Hessen-Kassel.11 In 1831 he moved from Leipzig to his new residence in Hanau. From there, the two paintings became part of the Hessische Hausstiftung, which formed part of the Museum Schloss Fasanerie in Eichenzell, in the district of Fulda.12 Both paintings are still on display there now, together with another painting by Ruysch. This third work by Ruysch was bought by collector Heinrich Wilhelm Campe in Munich, and ever since this purchase the three paintings have been together.13

31

Christian Friedrich Fritzsch

Frontispice from Johann Ernst Hebenstreit ''Museum Richterianum'' continens fossilia animalia vegetabilia mar, 1743

Mainz, Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz

Notes

1 Van Gool 1750-1751, vol. 1, p. 217.

2 On Gottfried Winckler: Schepkowski 2009, p. 59; exhibition Spuren. Die Sammlung Gottfried Winckler. Ein Leipziger Kunstfreund des 18. Jahrhunderts, Leipzig 2009; https://www.leipzig.de/news/news/spuren-die-sammlung-gottfried-winckler https://artmap.com/mbdk/exhibition/spuren-die-sammlung-gottfried-winckler-2009; http://museum.zib.de/sgml_internet/sgml.php?seite=5&fld_0=gm001453 (all consulted: September 2017).

3 Auction catalogue Sotheby’s London, Old Master & British paintings evening sale, 3rd July 2013, lot 29 (consulted September 2017).

4 Schepkowski 2009, p. 58-59. Sven Pabstmann is working on a PhD thesis on these two Leipziger collectors: https://www.svenpabstmann.info/ (consulted September 2017).

5 Heiland 1989, p. 139-174.

6 Many thanks to Andreas Dobler, Museum Schloss Fasanerie. Gleisberg 2000, p. 114-115 and the letter he wrote to Museum Schloss Fasanerie, 5th December 1999.

7 Auction catalogue Leipzig 1810, lots. 47 and 48. Ketelsen et al. 2002, p. 34.

8 An extensive catalogue of this collection was published by Johann Ernst Hebenstreit (1703-1757): Hebenstreit 1743.

9 Exhibition catalogue Verzeichniβ der Gemälde welche zum Besten unglücklicher, durch den letzten Krieg völlig verarmster Dorfbewohner vom 7. april bis zum 31. may 1814 offentlich ausgestellt sind, nos. 65, 70. And for more information about the Leipziger Völkerschlacht, see for example: https://historiek.net/volkerschlacht-slag-bij-leipzig/37595/ (consulted: October 2017).

10 Auction catalogue Verzeichniss der von Herrn Fischer, Kunstmaler zu Leipzig, hinterlassenen Original-Oelgmälde, Leipzig 8th May 1820 (Lugt 9791), lots. 64 and 65.

11 Auction catalogue Verzeichniss der Oelgemälde, Handzeichnungen und anderer Kunstgegenstände, Leipzig 1827 (Lugt 11539), lots. 43 and 44.

12 Many thanks to Andreas Dobler, Museum Schloss Fasanerie, for passing on the museum’s documentation.

13 This information is mentioned in the RKD’s copy of the 1827 auction catalogue.