4.1 Imported Netherlandish Artworks

Mecklenburg had good contacts with the Netherlands long before the 16th century. The country was just one of the regions along the Baltic sea that were culturally looking towards the west. Artworks originating from the Netherlands can be found in a number of religious institutions in Mecklenburg. Especially interesting is the handful of small private altarpieces of which the known provenance reaches back to the female cloister of the Holy Cross in Rostock [1-11].1 Most probably they were originally imported from Antwerp in the early 15th century and have been taken as rare examples of a cheap, export-oriented production that is otherwise almost completely lost to us.2

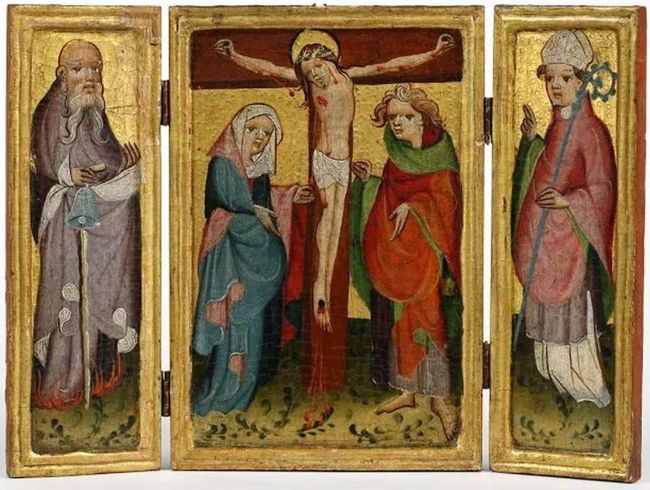

1

Anonymous, Antwerp, early 15th century

The crucified Christ with Mary and John on either side of the Cross

panel, oil paint 19,5 x 26,4 cm

Staatliches Museum Schwerin, inv.nr. G 2618

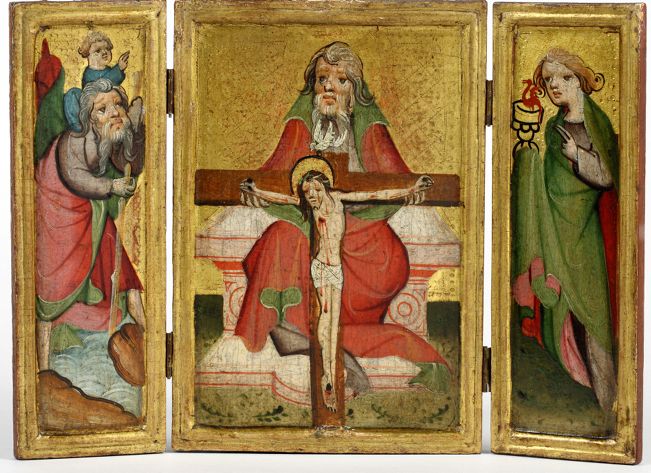

2

Anonymous, Antwerp, early 15th century

God the Father holding the crucifix

panel, oil paint 19,5 x 26,4 cm

Staatliches Museum Schwerin, inv.nr. G 826

3

Anonymous, Antwerp, early 15th century

The crucified Christ with Mary and John on either side of the Cross

panel, oil paint 19,5 x 26 cm

Staatliches Museum Schwerin, inv.nr. G 827

4

Anonymous, Antwerp, early 15th century

The crucified Christ with Mary and John on either side of the Cross

panel, oil paint 24,3 x 43 cm

Staatliches Museum Schwerin, inv.nr. G 828

5

Anonymous, Antwerp, early 15th century

God the Father holding the crucifix

panel, oil paint 25,5 x 32 cm

Staatliches Museum Schwerin, inv.nr. G 829

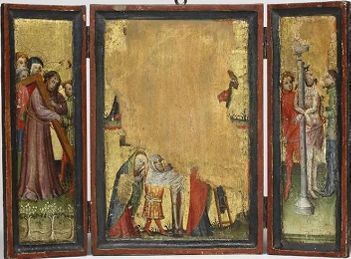

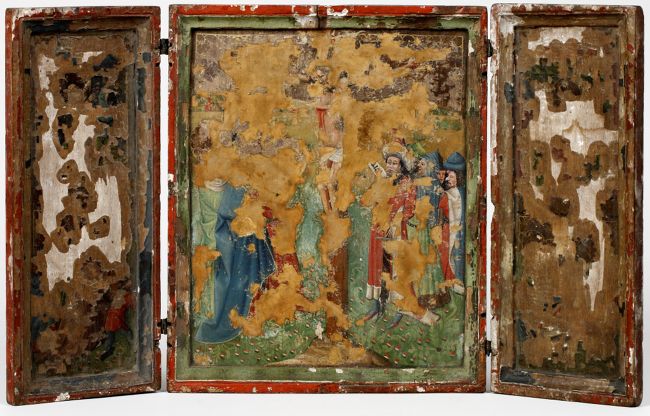

6

Anonymous, Antwerp, early 15th century

The Passion of Christ

panel, oil paint 27 x 34,6 cm

Staatliches Museum Schwerin, inv.nr. G 830

7

Anonymous, Antwerp, early 15th century

The Passion of Christ

panel, oil paint 39,5 x 40 cm

Staatliches Museum Schwerin, inv.nr. G 831

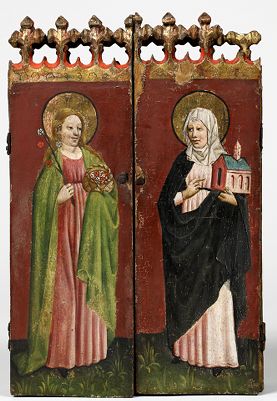

8

Anonymous, Antwerp, early 15th century

Reliquary with St. Catherine of Siena on the panel left, and St. Barbara on the right panel

panel, oil paint 31 x 41,6 cm

Staatliches Museum Schwerin, inv.nr. G 832

9

Anonymous, Antwerp, early 15th century

Two female saints

panel, oil paint ? x ? cm

Staatliches Museum Schwerin, inv.nr. G 832

10

Anonymous, Antwerp, early 15th century

Crucifixion

panel, oil paint 32,5 x 53 cm

Staatliches Museum Schwerin, inv.nr. G 2214

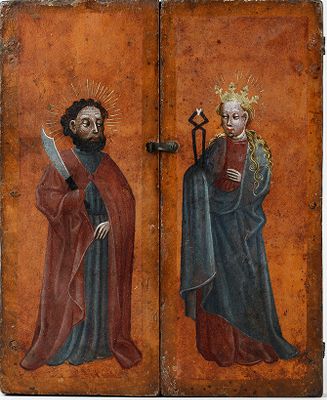

11

Anonymous, Antwerp, early 15th century

The apostle Bartholomew and Saint Apollonia of Alexandria

panel, oil paint ? x ? cm

Staatliches Museum Schwerin, inv.nr. G 2214

From the same cloister comes the wonderfully cheerful Christ child [12],3 a small sculpture from Mechelen from around 1500 for which the nuns have made clothes and a beautifully adorned crown – surely one of the highlights of the medieval collection of the Schwerin museum, even though the little cupboard filled with relics in which it was enshrined around 1625 was lost in the wake of World War II [13].4

12

Anonymous, Malines, c. 1500

The child Christ

wood, with clothes made in Rostock, 32 cm high

Staatliches Museum Schwerin, inv.nr. Pl 600

13

Reliquiary in which the Christ Child was kept, 15th century

wood and glass, 76 x 86 cm

Staatliches Museum Schwerin, inv. KK 8 (lost since 1945)

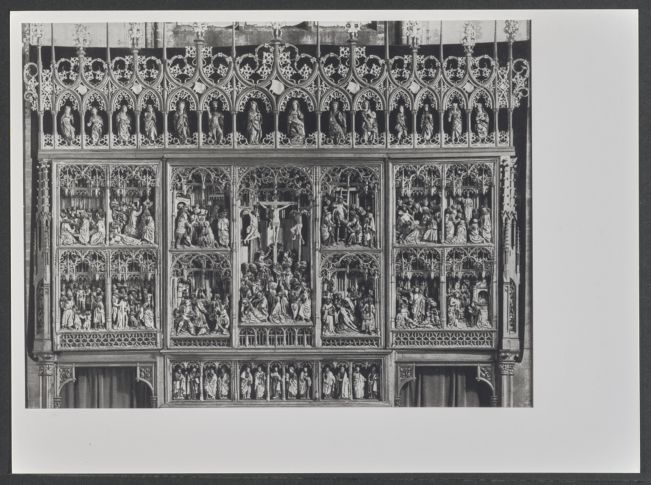

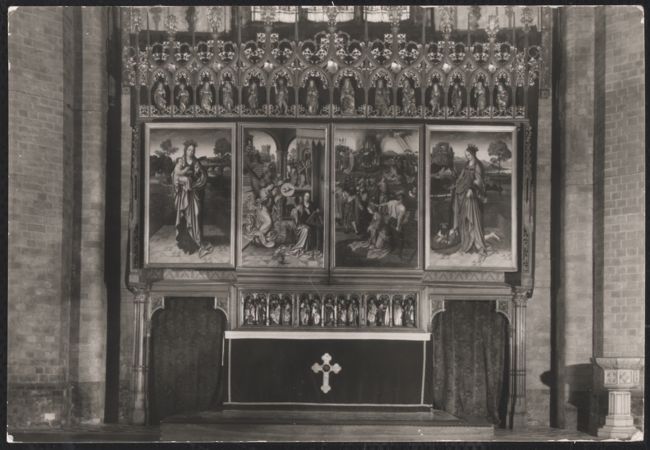

A much more formidable work of art taking us into the 16th century is the large altar piece by the Brussels wood carver Jan Borman III for the parish church in Güstrow [14].5 Even if the earlier attribution of the large painted figures on the double wings [15] to Bernard van Orley has long been refuted, it was an ambitious commission that must have been a civic statement vis-a-vis the near-by cathedral of the same city. On the other hand, the Dukes of Mecklenburg were also members of the Brotherhood of Saints John the Baptist and Catharine, which was probably the body that commissioned the altarpiece for the Güstrow church as Lisa Maria Vogel has shown.6 As high-ranking members of the brotherhood, the dukes were therefore directly involved in the highly prestigious project, which may, in the end, have been the reason that it survived the reformation which was introduced in Mecklenburg in 1549 by Duke Johann Albrecht I. The altarpiece is also interesting for the fact that some of its parts were sculpted and the whole of its sculptures painted only after it arrived in Güstrow. This makes a temporary presence of capable artisans from Borman's workshop in Mecklenburg most likely.7

14

Jan Borman (III) and studio of Jan Borman (III)

The Last Supper, the agony in the Garden, Ecce Homo, Christ before Pilate (interior left wing); Christ before Caiaphas, the carrying of the cross, the crucifixion, the descent from the cross, the lamentation (centre); The entombment, the resurrection, the appearances of Christ, the ascension (interior right wing), before 1522

Güstrow, Pfarrkirche St. Marien (Güstrow)

15

studio of Bernard van Orley (I) and Jan Borman (III) and studio of Jan Borman (III)

Virgin and Child; The annunciation, the presentation Mary in the temple and the marriage of Mary and Joseph; The martyrdom of Saint Catherine; Saint Catherine, before 1522

Güstrow, Pfarrkirche St. Marien (Güstrow)

Notes

1 Hegner 2015, no. 182-185 (inv. G 2618, 827, 826, 831), no. 187-190 (inv. G 829, 830, 828, 2214), no. 192 (G 832).

2 Two of these altar pieces, Staatliches Museum Schwerin, inv. nos. G 826, G 831, were included in the exhibition The Road to van Eyck (Kemperdick/Lammertse 2012, cat.nos. 56, 57).

3 Hegner 2015, no. 197.

4 Hegner 2009, Works of Sculpture, no. 80.

5 Roosval 1903, p. 24-26; Périer-D'Ieteren/Mohrmann et al. 2014. For an overview of the altarpiece, see RKDimages 281815.

6 Vogel in Périer-D'Ieperen/Mohrmann et al. 2014, p. 81-84.

7 Schöfbeck and Heusser in Périer-D'Ieperen/Mohrmann et al. 2014, p. 90-92. Compare also the new indications toward a slightly later dating than the hitherto current date of 1522 for the altarpiece, ibid. p. 91.