3.2 Trans-generational Mobility Patterns: the Le Blon and Sandrart Cases

The Le Blon and Sandrart families and their networks remained active as agents of cultural transfer between Germany and the Dutch Republic for generations, at least until the early 18th century. In the 1580s, they left their war-torn hometowns of Mons and Valenciennes and settled as merchants and artisans in Frankfurt. In Germany, members of the next generations became prolific artists and publishers. Despite their success and status in their new homes, they never lost touch with the Low Countries: for about four generations, they continued to move and travel between Amsterdam and Germany. Joachim von Sandrart (1606-1699) [1] is of course the best-known member of these families, but also his relatives, among whom Christof II (1593/1604-1665) and Michiel Le Blon (1587-1658) [2] and Lucas Jennis II (1590-after 1630), who was related to Le Blon and Von Sandrart by marriage, became successful intermediaries between the Dutch and German book and art markets and benefitted from their knowledge of both cultural regions. In many respects, Lucas Jennis laid the foundation for the publishing activities of Le Blon. Born in Frankfurt to parents from Brussels, he was also active as an engraver, a craft in which he was trained by Johann Theodor de Bry (1561-1623). Jennis published a wide range of book types and genres but specialized in alchemistic and hermetic literature as well as well as emblem books. In addition, his catalogue included translations of French and Italian novels, historical and art-theoretical works as well as several texts of Netherlandish and German medieval mystics, among whom Jan van Ruusbroec and Johannes Tauler.1

Between 1616 and 1631, Jennis published at least 233 titles in Frankfurt, but it is likely that this number was higher.2 Through his Dutch connections, especially Michel Le Blon, Jennis’s books also found their way to Holland, where new editions appeared in Amsterdam print shops. One of his contacts was the Frankfurt-born Bartholomeus Hulsius, a son of Flemish parents, whose religious emblem book Emblemata Sacra was published by Jennis.3 Trained and ordained as a Reformed minister, Hulsius first served the Dutch-speaking Austin Friars congregation in London and then moved to Cillaarshoek, a small village in the Rotterdam area. In the preface to the Emblemata Sacra, Hulsius explicitly addressed the Dutch Reformed community in London, to whom the book was dedicated. As one of the first Reformed religious emblem books in Dutch, the publication of the Emblemata Sacra was also a truly international project: written in Dutch, dedicated to an audience in England, and published by Jennis in Frankfurt, it reflected the diasporic outlook of seventeenth-century Netherlandish migrant circles in the North Sea area.

After Jennis’s death in 1631, many of his books were published by Christof Le Blon. Le Blon’s book catalogues included numerous French and Dutch works, some of which he translated into German himself. He also published translated foreign novels, especially of the pastoral genre, as well as topographies and travel accounts, such as Willem Ysbrand Bontekoe’s journal of his voyage to the East Indies. After 1650, he took over some of his father-in-law Matthäus Merian’s business and published more spiritualist and mystical literature.4 Besides works of medieval mystics, he also published controversial religious material, for example Schwenckfeldian texts and works with antitrinitarian leanings, which sometimes caused problems with Frankfurt authorities. Nevertheless, Le Blon stayed a member of the Reformed congregation of Frankfurt.

Like Jennis, Le Blon relied on his network abroad. Between 1659 and 1665 he cooperated with Amsterdam publisher Heinrich Betkius, originally from Germany, with whom he published ca. 30 titles.5 As Le Blon stated, his contacts in Amsterdam provided him with texts that could be of interest for the German market. In 1664, he published the Geistliche Schöpffung und Reise des wahren Israels aus Egypten (‘Spiritual creation and the journey of the true Israel out of Egypt’), a work in which Biblical history, especially the exodus from Egypt to Israel, was used as an allegory for personal spiritual development.6 In the preface to this book, Le Blon claimed that it was based on ‘an old Dutch manuscript of unknown authorship and origin’, which he had received from his brother in Amsterdam.7

This brother, whom Christof mentioned in his foreword, was Michel Le Blon who had moved to Amsterdam as a young adult and helped his Frankfurt relatives maintain close ties between Frankfurt and Holland. The exchange of texts between the two brothers was not limited to Dutch material and as ‘cultural brokers’ they were active in several directions: they translated foreign-language literature into German and vice versa: sometimes they published German texts in French, for example works of Jakob Böhme, sent to Christof by Michel from Amsterdam.8

Southern-Netherlandish networks of migrants and their descendants did not only inform the Le Blon brothers’ activities in Frankfurt, but also in Amsterdam. In Holland, where Michel Le Blon served as an agent for the king of Sweden, his personal network of friends and acquaintances consisted of many people with a Southern-Netherlandish family background, for example Abraham de Konigh, Jan Siewertsz. Kolm or Joost van den Vondel, who also wrote poems for Le Blon’s 65th birthday. It is also remarkable that Michel became a member of the Brabant migrant rhetoricians chamber ‘t Wit Lavendel rather than the native Holland chamber—apparently, even second-generation refugees still identified with the Southern-Netherlandish diaspora, regardless of whether they had grown up in Germany or Amsterdam.

Michel’s and Christof’s cousin Joachim von Sandrart benefitted from the transnational network of his relatives as well and he led an extremely mobile and itinerant life. Born to Walloon parents in Frankfurt, he lived in Utrecht and Nuremberg and then moved to Amsterdam where he stayed between 1637 and the mid-1640s.9 After his stay in Amsterdam, he resettled in his manor in Upper-Bavaria and then returned to Nuremberg where a Netherlandish migrant population had existed since the late 16th century. Sandrart’s Dutch connection continued to play an essential role in his work, which is also reflected by his ambitious book project, the Teutsche Academie der Edlen Bau-, Bild- und Mahlerey-Künste, the first encyclopedic history of art written in German.10 For this work, Sandrart drew from a wider range of literary and historiographical models but the influence of Karel van Mander’s Schilder-boeck played the most important role for the structure and concept of the book.11 In 1679, Sandrart also translated Van Mander’s Dutch paraphrase of Ovid’s Metamorphoses into German but through Sandrart’s reception of the Schilder-boeck, Van Mander indirectly laid an important foundation for German-language literature on the history and theory of the visual arts.

Among the next generations, many family members continued to move several times between the Rhine-Main area and The Dutch Republic. Even in the fourth migrant generation, we see that the same patterns were repeated and that the old connections to the Low Countries were still accessible. Christof Le Blon’s grandson, Jacob Christof Le Blon (1667-1741), born in Frankfurt and best-known for his invention of the four color printing press, followed his ancestors’ route to Amsterdam and in 1705 also married a Dutch wife, Gerarda Vloet. In Holland, he collaborated with local artists and writers and wrote an art-theoretical treatise in Dutch. He also had a minor role in the production of De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen (‘The Great Theatre of Dutch Painters’) by Arnold Houbraken, whom he had met in Rome. For this biographical encyclopedia on Dutch artists, Le Blon provided Houbraken with information on Netherlandish artists in Germany.12

1

studio of Joachim von Sandrart (I) after Joachim von Sandrart (I)

Self-portrait, after 1644

Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, inv./cat.nr. 1763

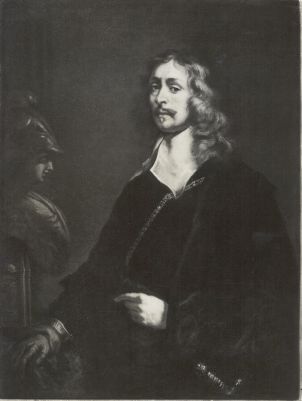

2

Theodor Matham after Anthony van Dyck

Portrait of Michel Le Blon (1587-1657), 1632-1676

Whereabouts unknown

Notes

1 Ruusbroec was published under the name of Johannes Tauler (Müller 2017, p. 12).

2 Based on the Frankfurt Messkataloge, Karl Gustav Schwetschke lists 233 titles published by Jennis but these catalogues do not always represent the total amount of publications of a publishing house. Schwetschke 1877, p. 65; 67; 71-78; 80-86.

3 13 Both/Stronk 2010, p. 73-102, esp. p. 92.

4 Deppermann 2002, p. 25-17. Most of the business of Matthäus Merian I (1593-1650) was taken over by his son Matthäus Merian II (1621-1687).

5 Schwetschke 1877, p. 95-99; 103; 106; 110; 127; 132.

6 Anonymous 1664.

7 Anonymous 1664, foreword, n.p.

8 Müller 2017, p. 9; 13.

9 According to his biography, his move to Holland was primarily motivated by the war situation in Frankfurt during the mid-1630s (Meier 2004, p. 220).

11 Meier 2012, p. 213-217.

12 Houbraken 1718-1721, p. 232-233; vol. 2, p. 280; 284; 287, vol. 3, p. 232-233.