1.6 The Mobility of German Artists to the Netherlands

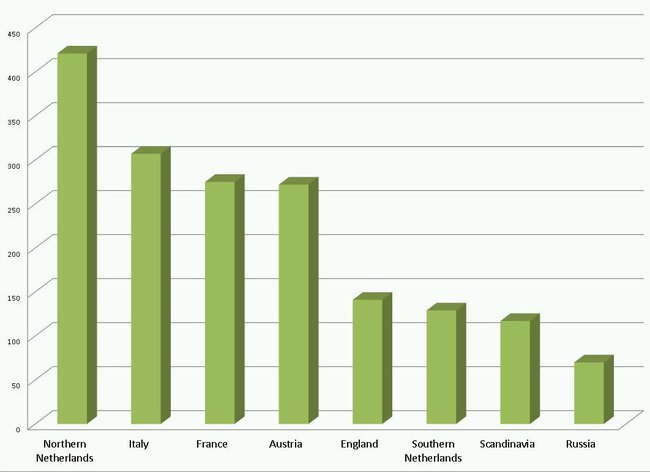

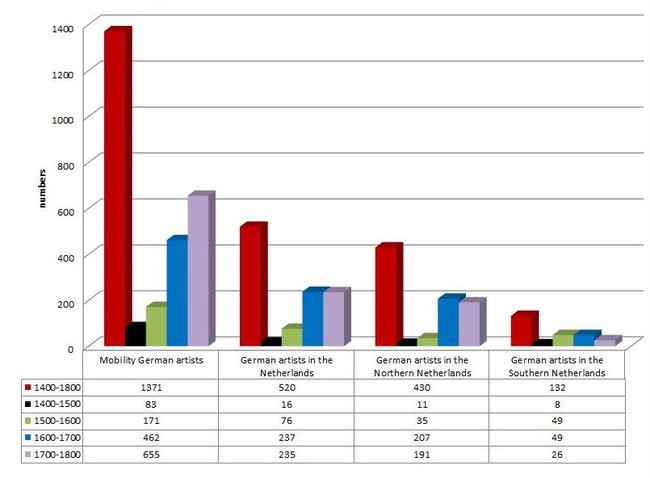

So far, I only spoke about mobility from the Netherlands, and not to the Netherlands. Was this preference of Dutch artists to migrate to the German lands mutual? We have seen before that German artists were even more mobile. How many of them went to the Dutch Republic? In the chart bar on the basis of RKDartists&, we see that the Northern Netherlands indeed was their first choice of destination outside the German lands [30]. It is striking that, as far as we know, the Southern Netherlands were far less popular among German artists, being number six in the ranking, after Italy, France, Austria and England. When we break down the mobility of German artists to the Northern Netherlands in centuries [31], we see that most of the migrations to the Northern Netherlands took place in the 17th century: almost 45% of the German artists who migrated abroad in that century chose to go to the Dutch Republic. In the 16th century, however, almost half of the German artists who left their homeland went to the Southern Netherlands, although the absolute numbers were much lower.

When we focus on the German artists who went to the Northern Netherlands, it appears that they originated from different places all over the region, although, as to be expected, more often from the north-west part. Just as Dutch artists went mostly to Hamburg, it is artists from Hamburg who are found mostly in the Dutch Republic. Frankfurt am Main and Emden also score highly as places of origin, followed by Cologne, Berlin, Augsburg and Nuremberg.1 Amsterdam was the main attraction for them, followed by The Hague, Utrecht, Haarlem and Rotterdam.2

As is mentioned above (§ 1.5), Brulez already claimed that the migration of German artists was mostly motivated by what he classified as ‘education’, indicating that German artists abroad were mostly apprentices and journeymen, the latter possibly being the largest group of the two. This claim is in line with the assumption in ‘social science migration research’ that tramping artisans’ journeymen, especially in the German-speaking world, were one of the largest groups of migrants in Europe in the early modern period.3 According to Ehmer (1997), the majority of apprentices and master artisans in German and Austrian cities and at least three-quarters of the journeymen consisted of immigrants.4 This migration system regulated the artisanal labour market. Naturally, the migrations were mostly not ‘transnational’, although many were and journeymen often travelled long distances. The same is true for journeymen painters in the Holy Roman Empire. Andreas Tacke at the University of Trier initiated several research projects on the training and working conditions of German painters before 1800, which shed some light on the rules and regulations of the guilds concerning journeymen in this sector.5 For centuries, the painters’ guild in most German towns made it mandatory for journeymen to spend two to four years as wanderers, sometimes even specifically abroad. When a journeyman returned home to become a master in the guild, he had to deliver a Meisterstück (‘master’s piece’), which had to prove what he had learned during his travels, after which, in the best case, he had to serve one or two years more for a local master, and in the worst case, was sent out to wander again. In every (German) town where a journeyman wanted to work, he had to show evidence of where he was born, a letter of apprenticeship and a journeyman’s certificate. Only in some towns – for instance Danzig, Leipzig and Nuremberg – the records of these documents have survived, making it possible to collect data on the places of origin. Even more scarce are documents providing insight into the mobility of individual journeymen, from their point of departure until their settlement as a master. In some rare cases a Stammbuch or album amicorum survived, making it possible to follow the journeyman’s trail, both geographically and socially.6

30

Destinations of German artists abroad until 1800

Source: RKDartists&, reference date April 2019

31

German artists who went to the Low Countries until 1800 1800

Source: RKDartists&, reference date April 2019

Maarten Prak, however, assumes that Dutch artists, in contrast to masters in the Southern Netherlands, hardly ever employed journeymen.7 In most biographical sources on artists the distinction between apprentice and journeyman is not indicated clearly, and lumped together as ‘training’.8 If journeymen from Germany indeed could not find work in the Dutch Republic, it must have been quite expensive for them to pursue their training here as an advanced pupil, although the costs may not have exceeded the costs of room and board if they were educated by a minor master. It is probably not a coincidence that it was the German Joachim von Sandrart (1606-1688) who wrote about the alarmingly high costs of being an advanced pupil in the Dutch Republic, for instance with Rembrandt (1606-1669) and Gerard van Honthorst (1592-1656), the latter being his former teacher.9 In the Latin edition of his Academia nobilissima Artis pictoriae (1683), Sandrart reported that Michael Willmann (1640-1706) [32] from Köningsberg had been deterred off by the training fees of well-known masters in Amsterdam and decided to use his money to acquire ‘prototypa’ (probably drawings and prints) and sell his studies to support himself, working day and night.10 One can imagine that journeymen who were forced to move on from one place to another, probably also to the Southern Netherlands, developed what Gerson called a ‘merkwürdige Mischstil’ (a peculiar mix of styles).11

Most German artists came to Holland when they were in their late teens or early twenties and were already trained to a certain extent at home.12 The only artist known to me who is actually said to have been active as a journeyman in Holland was Michael Neidlinger (1626-1700) from Nuremberg. Immediately after finishing his five years of apprenticeship with Georg Strauch (1613-1675), he went as a journeyman to work for Jacob Adriaenz. Backer (1608-1651) in Amsterdam in 1644, before moving on to Italy; still, it is possible that Neidlinger was not hired as such and had to pay for his ‘finishing school’. In the RKD dataset of 430 German artists who went to the Northern Netherlands in the early modern period, only 160 (37%) are listed with a name of one or more masters. Almost half of those (78, being 18% of the total) were trained in the Netherlands by a Dutch artist, as far as we know. Also, 153 artists who migrated from Germany (36%), remained in the Netherlands for the rest of their lives; 50 of them belong to both groups.

32

Michael Willmann

Susanna harassed by the Elders (Daniel 13:1-63), c. 1650-1653

Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, inv./cat.nr. Gm1402

33

Martin Faber

Self-portrait of Martin Faber (1586/87-1648) with maulstick, dated 1614

Marseille, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Marseille, inv./cat.nr. 465

34

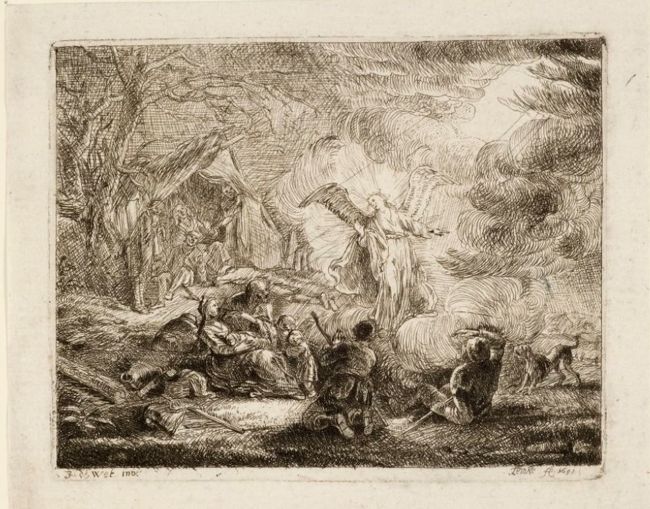

Johann Philip Lemke after Jacob de Wet (I)

The annunciation to the shepherds, dated 1651

Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, inv./cat.nr. 11384; V 3345

Some German artists were probably encouraged to go to the Netherlands because they received some prior training at home from a Dutch artist, which brings us back to the subject of professional chain migration. This was for instance the case with Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617), who was trained by Dirck Volckertsz. Coornhert (1522-1590) in Xanten; he followed him to Haarlem in 1577. Martin Faber (1586/87-1648) [33] received his first training in Emden from Johan Quant (active 1593-1620) from Groningen, before he moved on to study architecture in Groningen and later on became a pupil and/or assistant of the painter Louis Finson (c. 1575-1617) in Bruges. Johann Philip Lemke (1631-1711) from Nuremberg was initially apprenticed in Hamburg to German artists with first-hand knowledge of the Netherlands, namely Evert Decker († 1647), Matthias Scheits (c. 1625/30-c. 1700) and Jacob Weyer (1623-1670) before he went to Haarlem to learn from Jacob de Wet I (c. 1610-after September 1677) [34]. Lemke’s hometown teachers probably provided crucial information about the conditions in Haarlem.

Johann Gelle (c. 1580-1625) may well have attained Dutch contacts through his teacher Crispijn van de Passe I (1564-1637) in Cologne before he went to Amsterdam, and Maria Sybilla Merian (1647-1717) from Frankfurt was definitely informed by her teacher and stepfather Jacob Marrel (1613/14-1681), who travelled between Frankfurt and Utrecht many times during his lifetime. Her emigration to Holland must have been further facilitated by her half-brother Casper Merian (1627-1686), who had previously settled down in the Dutch Republic as an art dealer. However, although their training put them on the track, these artists did not move to Holland to learn, but to earn a living.

Still, according to our data in RKDartists&, 18% of the German artists who went to the Netherlands were trained there by a Dutch artist. Among them were the six German pupils of Rembrandt (1606-1669): Govert Flinck (1615-1660) from Cleves, in 1633-1635; Heinrich Jansen (1625-1667) from Flensburg, in 1645-1648; Frans Wulfhagen (1624-1670) from Bremen, in the 1640s; Christopher Paudiss (c. 1625-1666), who presumably came from Hamburg, from 1645 on; Johann Ulrich Mayr (1630-1704) from Augsburg, for a year in 1648-1649, after which he spent another year with Jacob Jordaens in Antwerp [35]; and finally Gottfried Kneller (1646-1723) from Lübeck, in the early 1660s, before he moved on to the studio of Ferdinand Bol.

Govert Flinck in turn, being of German origin himself, also attracted German pupils: Johann Spilberg II (1619-1689) from Düsseldorf in the late 1630s; Jürgen Ovens (1623-1678) from Tönning in Schleswig-Holstein;13 and Bartholomäus Hopfer (1628-1699), who was born in Amsterdam of German parents, between about 1642 and 1648. All of Flinck’s pupils, except for his own son, pursued their careers in Germany: Spilberg in his hometown Düsseldorf; Ovens in Gottorf and Friedrichstadt, not far from where he was born; Hopfer first in Augsburg, where his father came from and later on in Strasbourg. We do not know where Flinck’s pupil Johannes Buns came from, but after his training in Amsterdam he went to Cologne, where he became a master in the guild in 1668.

Gerard de Lairesse (1641-1711) had as much as seven (out of 19) pupils who were born in Germany. Again, there is a striking link with Hamburg: three of his pupils were born there – Philip Tideman (1657-1705), Hans Hinrich Rindt (1660-1750) and) and Ottomar Elliger II (1666-1732) – and the brothers Teodor (1654-1716) and Christoffel Lubieniecki (1659-1729) grew up in Hamburg. His pupil Bonaventura van Overbeek (1660-1705) came from Frankfurt, while Cornelis Huybert (c. 1669/70-after 1712) hailed from Emmerich.

35

Johann Ulrich Mayr

David with Goliath's head, c. 1650-1654

Augsburg, Deutsche Barockgalerie, inv./cat.nr. 8608

In summary, although it could very well be true that German artists mostly migrated to the Dutch Republic with the purpose to pursue their education, be it as a journeyman, ‘disciple’, or as an apprentice, this claim cannot be substantiated, because there are insufficient data available. However, as my data suggest, there are many indications that professional networks, especially master-pupil networks, were instrumental in the course of migrations of German artists towards the Northern Netherlands.

Notes

1 Birthplaces of German artists who went to the Northern Netherlands: Hamburg (29), Frankfurt (21), Emden (15), Cologne (10), Berlin (10), Augsburg (10) and Nuremberg (10). In her study of artist migration from North and East Europe to Amsterdam in the 17th century, Anna Koldeweij found Emden as the most common birth place, followed by Hamburg, and a much lower number for Frankfurt (Koldewij 2016, esp. p. 176). Her dataset however consisted for about two-thirds of artisans (especially gold- and silversmiths) and one third painters.

2 Destinations of German artists who went to the Northern Netherlands: Amsterdam (208), The Hague (77), Utrecht (34), Haarlem (25), Rotterdam (24).

3 Ehmer 2000, Reith 2006 and Ehmer 2011.

4 Ehmer 1997, p. 172; Ehmer 2000, p. 100.

5 Resulting recently in the exhibition Meisterstücke : Vom Handwerk der Maler, in collaboration with Wolfgang Cillessen (Cillessen/Tacke et al. 2019-2020).

6 Tacke 1997, p. 52-55, Tacke 2017.

7 Prak 2007.

8 On the role and status of painter’s journeymen and apprentices in the Low Countries: Peeters et al. 2007.

9 De Jager 1990, p. 77

10 Klessmann/Steinborn et al. 1994, p. 7 (German translation of the passage in the Latin text).

11 Gerson 1942/1983, p. 270; Gerson/Van Leeuwen et al. 2017, § 5.6

12 Walczak, for example, refers to all artists from Hamburg in his article as journeymen (Walczak 2011).

13 On the Dutch and Flemish influence on Ovens’ work, see the contribution by Patrick Larsen (§ 13).